It’s the Best of Bobwhite Quail Hunting

Bob McNally 10.27.15

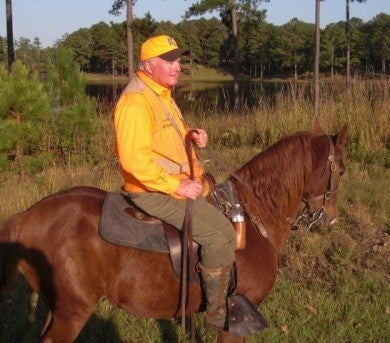

If horse racing is the sport of kings, than hunting quail from horseback must be what the monarchy does when not hugging the finish line at Churchill Downs.

And in the lush-green rolling hills of east-central “Black Belt” Alabama, hunters in traditional upland sporting garb pursue what arguably is the most storied and gentlemanly of American game birds: the bobwhite quail.

Nestled down a quiet, shady gravel road just a few miles from Union Springs is 500-acre Shenandoah Plantation, which offers wingshooters a taste of what bird hunters 100 years ago routinely experienced: using horses to follow far-ranging pointing dogs until they locate and lock-on point coveys of quail.

Horses are used to keep pace with high-strung and highly-trained pointers until they slam into muscle-stiff points, indicating the place where bobwhites are hiding in thick cover. Then horseman hunters trot to the spot, dismount, retrieve 20-gauge double shotguns from saddle scabbards, and flush and shoot quail.

This is rare sport available today, partly because of diminishing bobwhite populations, the cost of maintaining quail habitat, and training and owning hunting dogs, horses, etc. It’s hunting described by the elite of Old South sporting writers such as Havilah Babcock, Corey Ford, and Robert Ruark. Yet for a price it’s still available to upland sportsmen who’ve read about such gunning and want to cross it off their life bucket list at a place like Shenandoah Plantation.

The entrance to Shenandoah offers a hint of what visitors are about to enjoy. A modest stone facade bearing Shenandoah’s name marks the way in, with appropriate decorative fall flowers and pumpkins nearby. To the side and prominently in front of the sign is a life-size, perfectly-painted statue of a mostly-white English pointer, locked into a stylish tail-high point. The message is subtle, but clear: this is bird dog country, because it is bobwhite heaven.

Quail hunting tradition is long and storied in the 23 counties that make up the so-called Alabama “Black Belt” area. In Union Springs there is a life-size bronze statue of an English Pointer in rigid, stylish point. It’s in the heart of town and proudly proclaims the region as the “Bird Dog Field Trial Capital of the World.”

This area’s remarkably fertile land is affectionately known as Alabama’s “Black Belt” because the dirt is dark and rich, and from it grows some of the most ideal quail habitat known. Rolling carpets of chest-high broomsedge grow among vast stands of manicured pine trees, creating quail havens unknown to most other regions today.

The area also boasts some of America’s most abundant deer herds, and hunting for whitetails (plus pheasants, ducks and turkeys) is available on plantations such as Shenandoah throughout the region.

I arrived at Shenandoah about mid-day, meeting friends Glenn Wheeler of Arkansas and Jeff Dennis of Charleston. We were greeted by Shenandoah’s head man Robert Moorer and plantation dog handler Kenyatta Harris. After settling into the plantation lodge beside a sprawling 40-acre lake (loaded with bass to 13-pounds and bream), we ate a fast lunch then loaded up for hunting.

We headed afield via horseback, on spirited but friendly animals. Trailing behind was a wagon with specially-designed kennels that held pointers and spunky Boykin spaniels.

The rolling quail land of Shenandoah is manicured with plantation roads and grass lanes that cut through dense cover and broomsedge-pine stands where bobwhites thrive. It makes for comfortable horseback riding and good access for gun dog wagons.

We were only a few hundred yards from Shenandoah’s lodge when a pair of white pointers were taken from their kennels and released. In a flash they raced ahead of our horses and wagon, coursing far afield left and right of our crew.

Ten minutes later one of the racing dogs tipped his head high, cut right down a wide path, and near a tangle of cover stopped ridged, tail high, body solid as stone. Moments later the second pointer showed on the scene and immediately slammed into a “backing” point in a classic show of bird dog professionalism.

Dennis and I dismounted (only two hunters are allowed on the ground at a time for safety), removed shotguns from saddle scabbards, and loaded them. We moved quickly to either side of the pointers to flush birds that the dogs showed where holding nearby.

Then the ground blew up into a feathered frenzy covey of twisting, turning brown rockets. They zigzagged in 20 different directions, zipping wide and far at speeds seemingly impossible to track with a shotgun.

We each fired twice, and somehow two birds went down, which were quickly retrieved by a Boykin spaniel released by Harris.

“Our dogs are specialists,” said Moorer. “Pointers find quail, Boykins retrieve them. It works well, and the dogs understand their jobs.”

We spent the afternoon covering much of Shenandoah’s quail ground, locating, flushing, and shooting birds until long shadows fell across rolling hills and the cool of evening arrived.

At the last covey point on a knoll overlooking the plantation lake, Dennis and I walked from our horses to the pair of pointers holding rigid ahead. Low, but bright sunlight highlighted the dogs, and at that very moment a fish feeder beside the lake automatically went off, sending pellets far and wide across the water.

Instantly big bream and oversize bass began boiling the surface as they gorged on broadcast fish food.

“You can fish after we’re done hunting quail, it’s pretty good about dusk,” said Moorer.

“It’s good to be king,” replied Dennis smiling, as he took a step toward the pointers and the world blew up again with bullet-quick bobwhites.