Blackpowder Guide, Part 3: Gun Powder & Primers

Travis Olander 01.02.24

In part 2 of our guide to blackpowder guns, we covered one half of the accuracy equation: projectiles. The powder and primers you use to send your rounds downrange matter just as much. The right combination will ensure you get appropriate chamber pressures – not too much, which can be catastrophic, and not too little, which results in poor performance – to produce optimal velocities and accuracy downrange.

Blackpowder Content on AllOutdoor

- The Evolution of Blackpowder for Muzzleloaders over the Years

- Top 5 Modern Muzzleloaders for Blackpowder Hunters

- Federal FireStick Legalized for More Muzzleloader Seasons Across the US

- Ringing Steel at 1,780 Yards with a .40 Cal Muzzleloader?

Picking Blackpowder

Picking the right powder for your muzzleloader means considering three key choices:

- Picking powder or a powder substitute

- Selecting a granulation size of each grain

- Selecting loose-pour or pelletized powder

Blackpowder vs. Powder Substitute

Traditional blackpowder is highly reactive. It ignites easily, making it the preferred choice for traditional muzzleloaders using external percussion caps or flintlocks for ignition. But traditional powder is also high corrosive. Extensive cleaning is required after each use, lest you suffer a severely pitted barrel and chamber. Blackpowder substitutes are preferred because they’re less corrosive.

In many cases, substitutes have become more popular than traditional powder. If you prefer less cleaning and maintenance, it’s worth giving a substitute propellant a try. But, if you find you’re struggling with ignition when firing a flintlock or traditional percussion rifle, regular ole’ blackpowder may be the solution.

Pyrodex

Pyrodex, the most common and affordable substitute, uses a lower percentage of sulfur and saltpeter, while incorporating over compounds, like potassium perchlorate, sodium benzoate, and dicyandiamide. Although combustible, these compounds are less sensitive to ignition sources, making them safer to transport and handle. When ignited, Pyrodex is, in fact, more energetic per unit of mass than blackpowder – but, because this powder substitute is lower in density per cubic inch, its net energy release means it can be easily substituted for blackpowder using a 1:1 ratio. In other words, a rifle that calls for 90 to 150 grains of black powder can also be filled with exactly 90 to 150 grains of substitute, and still achieve the same level of energy. Pyrodex costs, on average, the same per unit as blackpowder: About $19 to $23 per pound.

777 (“Triple 7,” or “T7”) Substitute

Triple 7 powder is considered a higher-quality propellant substitute to Pyrodex. Shooters claim Triple 7 leaves behind less residue than Pyrodex and generally makes swabbing the bore and removing fouling an easier task. But T7 propellant is more expensive, too. Triple 7 is, on average, roughly 50% costlier than black powder an Pyrodex, averaging $33 to $35 per pound.

Blackhorn 209 Substitute

Blackhorn 209 is considered the highest quality, and most expensive, propellant substitute. It’s significantly costlier than Triple 7, blackpowder, and Pyrodex. But those willing to spend the money – up to $75 for half a pound – claim that it provides noticeably better accuracy and performance, with higher velocities pound-for-pound than any other propellant, including blackpowder. Blackhorn 209 is also nearly smokeless, providing a clean burn and leaving behind little to no residue nor fouling.

But, like most topics concerning the function of firearms, propellant selection and the resulting performance is often subjective, or at least unique to the gun, the shooter, and the projectile. It’s best to test various propellants to confirm which provides the best balance of cost, performance, and cleanliness.

Blackpowder Grain Size

Grain size plays an important role in any powder’s combustibility: the smaller the grain size, the more surface area there is, relative to the total mass of the powder. That means the smaller the grain size, the faster the powder turns. Grain size is just one factor of the equation. There are simply too many other factors – grain shape, density, graphite content and powder purity, inclusions of creosotes, burn temperature – to rely solely on powder granule size to determine performance. But follow the general guidelines below, and you’ll have consistent performance without the risk of blowing up your barrel. For traditional black powder, grain size is measured by F’s: One “F” on the label denotes a coarse grain. The more F’s on the label, the finer the grain

- Fg: The coarsest grain. Used in hobbyist cannons, muskets, and rifles with a bore diameter of .75 or greater. It’s also used for shotguns that are 10-gauge or larger.

- FFg: Medium grain. Used for rifles with bore diameters of .50 to .75. Also used for 20- to 12-gauge shotguns, and pistols with bores .50-cal or greater.

- FFFg: Fine grain. Used in all blackpowder guns with calibers below .50.

- FFFFg: Extra-fine grain. Used as a primer powder for flintlock pans. Do not use FFFFg powder as a primary charge — you’re likely to experience a catastrophic failure.

Powder substitutes are even simpler, and are marked by the following:

- RS: Used for rifles and shotguns. Equivalent to FFg powder.

- P: Used for pistols. Equivalent to FFFg powder.

Loose vs. Pelletized Powder

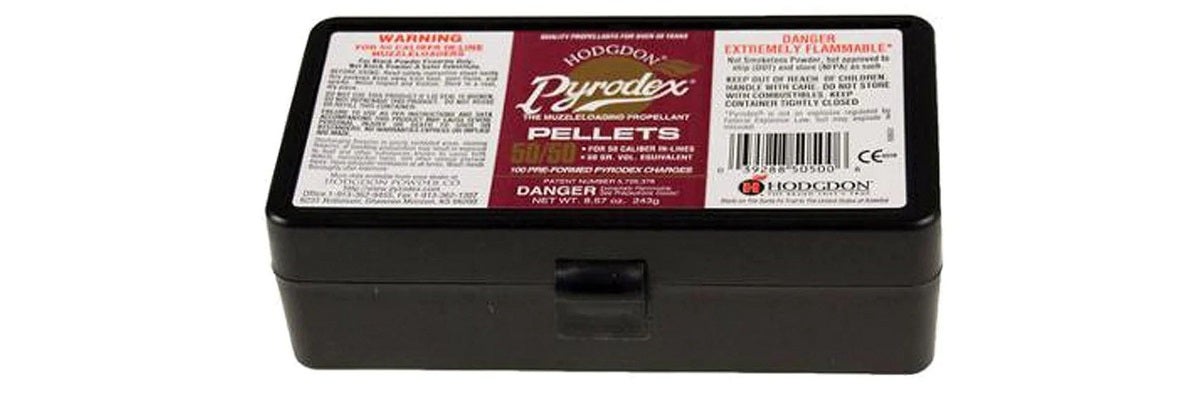

Pelletized powder affords one advantage: convenience. Individual pellets are formed to hold a particular number of grains, which affords easier measuring. They’re also quicker to load and require no powder measure or flask. But pellets provide no measurable benefit over loose powder when it comes to ignition, velocity, and accuracy. Pelletized powder is also costlier than loose powder.

Primers & Percussion Caps

The primer or cap used to ignite your powder charge is as important as the powder itself: a hot, consistent ignition temperature ensures a quick and consistent charge burn, producing predictable velocities, which translates into better accuracy. Save for flintlocks, which rely on loose pan powder, there are three types of igniters used for all muzzleloaders: The modern 209 primer, large rifle primers, and traditional percussion caps.

209 Primers

The 209 primer was adopted by the muzzleloading world to provide hotter burns and more reliable ignition than traditional caps. They’re used in all inline muzzleloaders, and some traditional muzzleloaders that would otherwise use a cap are now being made to accept 209 primers. The 209 is used as the primer for modern shotgun shells. This mass production makes it an inexpensive option for muzzleloader ignition. 209 primers are made as magnum primers and standard primers. The former is suitable for igniting less reactive substitutes (like Blackhorn 209) and pelletized powder, which can be more difficult to ignite. Standard primers are suitable for traditional blackpowder, Pyrodex, and Triple 7.

Large Rifle Primers

The VariFlame conversion kit is a relatively new system that enables a muzzleloader to use a large centerfire rifle cartridge primer for ignition. These modern primers burn hotter and faster than 209 primers and caps. Currently, this system is designed for the Paramount Pro Series Rifles from CVA. These rifles are made to burn large powder charges to obtain incredibly high muzzle velocities (up to 2,200 FPS), affording sub-MOA accuracy at 300 yards or more.

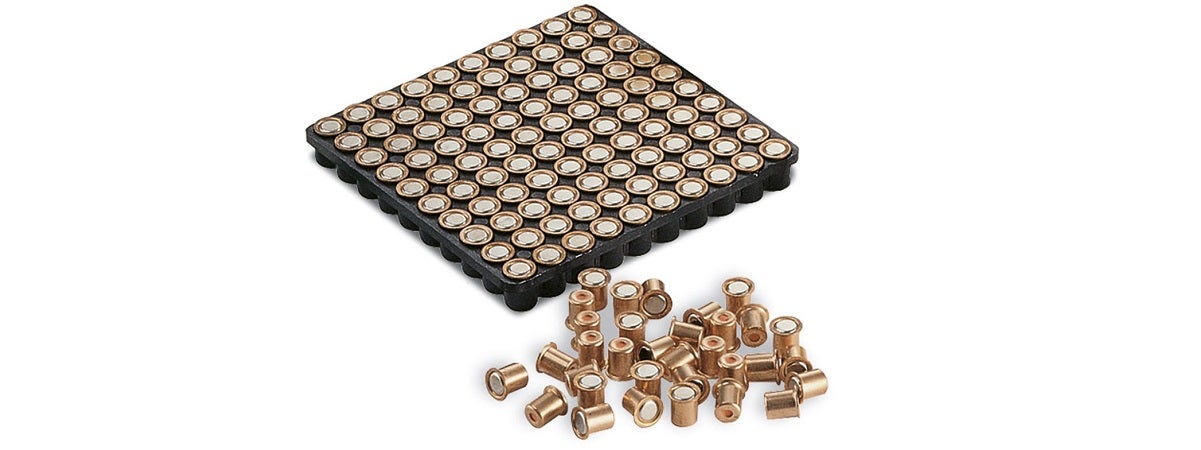

Percussion Caps

Percussion caps were the original primers used on traditional muzzleloaders, replacing the flintlock action in the early 1820s. They’re still used today for traditional percussion handguns and long guns, including reproduction rifles and muskets. There are three common percussion cap sizes: #10 caps, which are used primarily for pistols; #11 caps, which are used for rifles; and musket caps, which are, as the name implies, are used on smoothbore guns.