.270 Win vs .308 Win: Is Smaller & Faster Really Better?

Travis Olander 12.15.23

These two centenarian game cartridges have been used by hunters and marksmen alike, affording good accuracy at distance, with modest felt recoil and relatively lightweight actions and barrels. Both rounds are so popular that most of your favorite bolt guns have been chambered in them: The Remington 700, Tikka T3, Savage 110, Weatherby Mark V, and dozens of other rifles from Howa, Mauser, Christensen Arms, Mossberg, Sig, Kimber, and the like offer tactical and hunting rifles in .270 and .308.

.270 Winchester is Better, but it Might not Matter

The .308 camp will be mad at this statement of fact. But, oh well: Although .308 Winchester — and its military counterpart, 7.62×51 NATO — is by far the more popular cartridge (and still one of the most popular rifle cartridges, ever) it’s the smaller, faster .270 Winchester that provides superior performance. But whether this performance even matters is debatable. Let’s explain.

.270 Winchester Specs

- Bullet Diameter: .277″

- Case Length: 2.54″

- Overall Length: 3.34″

- Case Capacity: 67 gr H2O

- Common Weights: 90, 130, 140, 150 grains

.308 Winchester Specs

- Bullet Diameter: .308″

- Case Length: 2.015″

- Overall Length: 2.8″

- Case Capacity: 56 gr H2O

- Common Weights: 125, 150, 168, 175, 185 grains

.270 Winchester: Brief History

Though .308 Winchester is considered archaic by some, .270 Winchester predates it by at least two decades. The smaller cartridge was invented when Winchester’s engineers necked down the .30-06 cartridge, capped it with a .277 bullet to obtain performance similar to the 7mm Mauser, and chambered it in their then-new bolt action, the Model 54, with an action based heavily on the Mauser 98 action. The Model 54 was Winchester’s first successful civilian production bolt gun.

In spite of its high velocity and flat trajectory, the .270 Winchester wasn’t received with wide favor. It wasn’t until Jack O’Conner, famed big game hunter and literary, praised the cartridge for its accuracy and performance in the field.

.308 Winchester: Brief History

The .308 Winchester is the civilian counterpart to the 7.62x51mm NATO cartridge. Developed in the 1950s, the short-action .30-caliber cartridge was made to shave weight and provide higher capacity for intermediate service rifles. In 1952, Winchester developed the civilian version of the round and marketed the cartridge to American hunters. Although identical at appearance, the .308 Winchester is a hotter cartridge. It’s loaded to higher pressures with a thinner casing wall.

Because of this, .308 Winchester-chambered rifles can safely shoot 7.62×51 NATO, but the inverse isn’t true. NATO chambers should not be loaded with .308 Winchester. Unlike the .270’s slow adoption, the .308 quickly became one of the most popular rifle cartridges ever made. It was, at the time, one of just a few short-action rounds that afforded smaller and lighter rifles, while providing high velocity and relatively little bullet drop out to 300 yards.

.270 Win vs .308 Win Ballistics

Like I said earlier, .270 Winchester is objectively a superior round when compared to .308 Winchester: It affords less bullet drop at comparable distances, with higher energy and better ballistic coefficients. But is investing in a larger, heavier, more expensive long action worth the added performance? Let’s crunch the numbers.

150-Grain Loads Compared

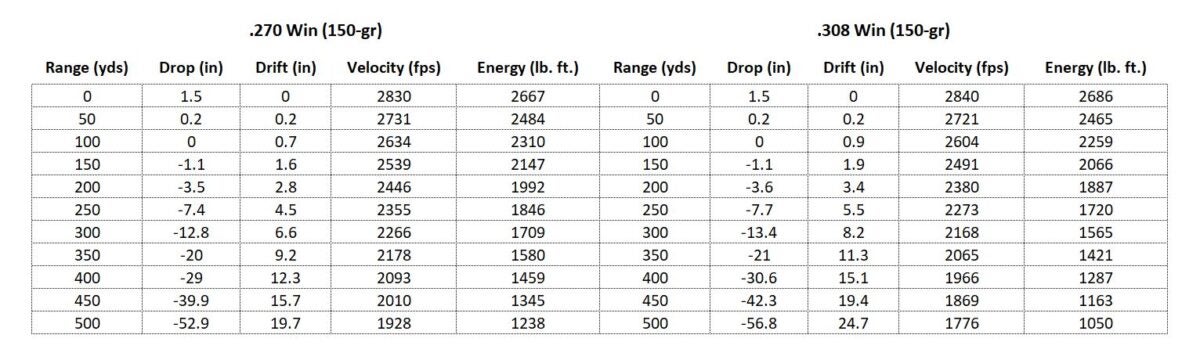

Comparing these cartridges’ identical grain weights gives us the best picture — but keep in mind that 150 grains is about the limit of what .270 cartridges can handle; this is considered middle of the road for .308 Winchester.

.270 Winchester

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,830 fps

- Energy @ 300 yds: 1,709 ft-lb

- Drop @ 300 yds: 12.8 inches

.308 Winchester

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,840 fps

- Energy @ 300 yds: 1,565 lb. ft.

- Drop @ 300 yds: 13.4 inches

Off the bat, we can see both rounds have practically identical muzzle velocities. But, because .270’s lighter, it retains more of its initial energy downrange and winds up retaining an extra 144 lb. ft. of energy at 300 yards — that’s about 10% additional power at the maximum distance that most folks feel comfortable taking shots when hunting. Bullet drop differences are also negligible; .270 Win beats out .308 with about half an inch (4.5%) less drop at 300 yards.

If we follow .308’s path out to 500 yards, we find it still only suffers marginally worse performance: About 7% additional bullet drop, at 3.9″, and it retains about 15% less power, or 188 lb. ft. But it’s the differences in wind drift that illustrate how .270 Winchester excels downrange.

Beyond just 100 yards, .270 Win suffers between 15% and 20% less wind drift, which equates to about 5″ of drift at 500 yards. That’s not insignificant, particularly if you’re shooting at typical 12″ silhouettes, or trying to lung a deer just behind the shoulder. We can also infer this difference grows to become problematic for .308 Winchester at 800 to 1,000 yards, significantly impacting hit probability for the NATO-born cartridge in the presence of any wind.

Heavier .308 Gains an Edge

Heavier grain weights can compensate for one caliber’s comparatively inferior performance. One of .308’s heaviest loads, 178 grains, suffers poorer muzzle velocity, but it provides better energy retention and significantly improved bullet drop. Wind drift is also mitigated. Let’s compare again:

.270 Winchester (150-grain)

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,830 fps

- Energy @ 300 yds: 1,709 ft-lb

- Drop @ 300 yds: 12.8 inches

.308 Winchester (178-grain)

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,600 FPS

- Energy @ 300 yds: 1,792 lb. ft.

- Drop @ 300 yds: 8.8 inches

At the 300-yard measurement, we find 178-grain .308 provides about 83 lb. ft. (roughly 5%) more energy than .270 Winchester’s 150-grain load. Bullet drop is improved noticeably, though. The .308 drops 4 inches less, a roughly 31% reduction.

Is .270 Really Superior?

Practically speaking, 270 Winchester is only marginally better than .308 Winchester. Within 300 yards — the distances that virtually all hunters take their shots — the two rounds are so closely matched that either cartridge’s bullet drop and wind drift provides no meaningful advantage over the other, regardless of grain weight.

At long-range distances, .270 Winchester provides noticeably better wind drift resistance and moderately improved bullet drop; in short, it shooters flatter. But then the argument that there are far superior short- and long-action cartridges to pick for this type of shooting — like any of the 6.5mm series loads developed over the past 30 years — enters the discussion (but that’s a topic for another day).

So, we look to the non-performance topics that might sway you to consider .270 over .308. It’s here that you might find reasons to stick with .308.

Felt Recoil

Felt recoil goes to .308 Winchester — but again, both are closely matched when looking at similar grain weights. In an 8-pound rifle, a 130-grain .270 Win load generates about 18 lb. ft. of recoil energy. The lightest .308 load (125 grains) generates just 9 pounds of recoil energy, while the common 165-grain load generates 18.1 lb. ft. of energy; basically identical to the .270.

Terminal Performance

It is inarguably that, unless a lighter round is travelling significantly faster, it’s the bigger round that produces a bigger hole. The .308’s heaviest loads to, in fact, punch game with more energy and more bullet to boot. Although .270 is perfectly capable of taking most antlered game without a chase ensuing, the .308 may drop a large bull elk or moose more effectively.

Short vs. Long Action Guns

Short-action rifles are simply cheaper, lighter, and easier to shoot, and there’s a legitimate argument for sticking with .308 Winchester for this reason alone. Sure, the argument can be made that a long action soaks up more felt recoil — but in this case, .308 wins with a generally softer punch to the shoulder, anyway.

Cost Per Round

At publication, .308 Winchester remains the most popular and commonly sold .30-caliber rifle round on the market. It will likely remain more affordable on a per-round cost basis than .270 Winchester, well, forever.

The average cost per round for .308 ranges between $0.66 and $0.90 for typical FMJ brass, while Match Grade ammo average $2.00 to $2.50 per round.

The current cost per round for typical FMJ .270 ranges between $0.90 and $1.50, while Match Grade loads average about $2.00 to $3.00 per round.

Practically Speaking, It’s a Wash

It is true that .270 Win outperforms .308 Win on paper — particularly where wind drift is concerned, especially at greater distances. But the advantages gained in ballistic performance with the latter are a moot in the context of most practical applications:

Both rounds are made for hunting, where virtually all shots will be taken well within 300 yards. Here, .308 Winchester’s marginally worse ballistic performance is negligible and, in fact, its heavier loads might provide better performance, plus more knockdown power.

Couple these facts with the other benefits .308 provides — better felt recoil with lighter loads, the advantages of a short action, arguably better terminal performance, and a lower average cost per round — and you might conclude it’s better to stick with the larger of the two cartridges. In this case, .270 Winchester may only be preferable if you’re often ringing steel beyond 500 yards.

Of course, the quality of the rifle matters as much as the round. Check out MDT’s new TIMBR Frontier Stock, made for the .270- and .308-chambered Remington 700, Tikka T3, and Tikka T1X.