The State of Chronic Wasting Disease in U.S. Deer

Travis Olander 01.29.24

It’s 2024, and most states have ended their deer seasons for hunters. Although not yet endemic to all 50 states, Chronic Wasting Disease – an infectious, as yet incurable prion disease with a guarantee of fatality in cervids – continues to slowly but surely spread. Researchers have raised alarms about its potential to become transmissible across species, new states have seen their first cases in CWD in recent years, and other states, wherein the disease is minimally present, are now attempting to contain the spread. This is the state of Chronic Wasting Disease as we head into 2024.

Which States Have Chronic Wasting Disease Infections

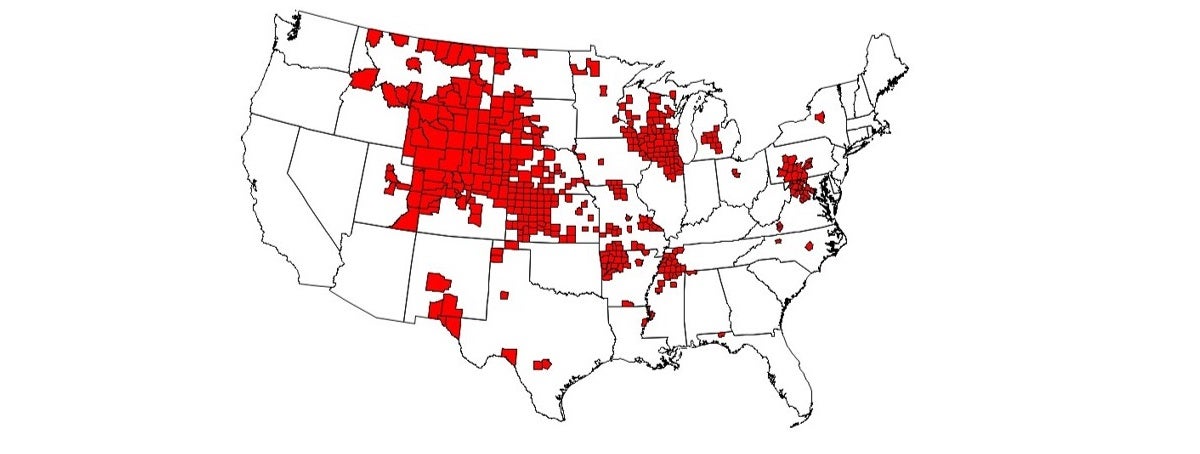

As of November 2023, Chronic Wasting Disease has been found in deer, elk, and moose in 31 states across the U.S. It has also spread across the norther borders into three provinces in Canada. CWD was first identified in the 1960s, at a research facility in Colorado breeding captive deer. In 1981, the first cases in wild cervids were confirmed.

Although present in 31 states, CWD remains concentrated in just a few: Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Arkansas comprise the most counties reporting infections spread from the original source of outbreak, with separate, isolated clusters of concentrated infections also present in Missouri, Wisconsin, and Illinois and central Pennsylvania, Maryland, and northern Virginia and West Virginia.

In regions with dense infection, the positivity rate can exceed 1 in 10 to 1 in 4 deer. Organized slaughters have been necessary to cull captive deer populations wherein the infection rate approached 4 in 5 animals. As of November 2023, these are the 31 states now confirmed to have deer and other cervids infected with CWD. Each state is listed with the number of counties containing infections:

- Alabama (1)

- Arkansas (19)

- Colorado (27)

- Florida (1)

- Idaho (1)

- Illinois (19)

- Iowa (12)

- Kansas (49)

- Louisiana (1)

- Maryland (2)

- Michigan (10)

- Minnesota (8)

- Mississippi (9)

- Missouri (27)

- Montana (24)

- Nebraska (43)

- Oklahoma (1)

- New Mexico (3)

- New York (1)

- North Carolina (2)

- North Dakota (7)

- Ohio (2)

- Pennsylvania (14)

- South Dakota (20)

- Tenessee (15),

- Texas (8)

- Utah (8)

- Virginia (5)

- Wisconsin, (41)

- Wyoming (22)

States With Fewer Infections Battle Spread

States in which infections of CWD are fewer have proactively enacted sampling and containment programs to attempt to restrict the spread of the disease. In Idaho, two of 76 zones contain all the state’s infected deer. These two locales – zones 14 and 15 – have been designated CWD management areas. Here, hunters are required to submit all cervid kills for testing: Lymph nodes are to be removed and provided to a check station or drop-off location; samples are tested by Idaho Fish and Game. Spinal cords and deer heads must be disposed of, and cannot be removed from the area. Whole carcasses cannot leave the zones. Authorities in Idaho have also approved deer cullings outside regular hunting seasons, working closely with private land owners and hunters to contain the spread of infectious deer.

Idaho’s containment procedures have thus far proven effective, with no infections reported outside the two original zones with confirmed disease. Testing and monitoring continues to take place throughout the state to identify any potential spread beyond the containment areas. Texas saw its first cases of Chronic Wasting Disease in 2012 and has since enacted its own CWD management areas to contain the spread. In August 2023, the first case of disease indicating spread beyond outbreak sources was confirmed when a captive white tail was tested postmortem and confirmed positive. In response, the state’s wildlife department proposed new surveillance zones around the positive facility to ensure the disease doesn’t become endemic to larger regions. The new proposed zone encompasses roughly 90,000 acres, or 140 square miles. Elsewhere in Texas, researchers are taking a more novel approach to quelling the spread of CWD.

How Scientists Are Trying to Stop the Spread of Chronic Wasting Disease

Dr. Chris Seabury, a genetics professor at Texas’ A&M School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, believes Chronic Wasting Disease can be contained by breeding deer that have natural, partial immunity to infection.

“CWD risk and the incidence of CWD can be predicted with high accuracy regardless of the origin, whether it’s through infectious exposure, the normal classical route or whether it’s sporadic,” Seabury said. “We do think sporadic cases can happen. They happen in other species.”

Seabury’s research centers on assessing individual deers’ genetics to determine how susceptible that deer is to infection from exposure. By selectively breeding deer with genetics that display resistance to infection, Seabury says the chances of infection can be significantly reduced. Complete eradication of the disease through selective breeding may not be possible – but it may not be necessary, either.

“Selective breeding significantly reduces CWD susceptibility. That can be tested as a hypothesis and proven to be true,” Seabury said. “Total breeder depopulation is often unnecessary. We have a demonstration project. We’ve already shown that to be true.” Seabury’s research is what spurred the state to approve a pilot project breeding CWD-resistant deer at a facility in South Texas in 2021.

Using Rapid Testing on Live Populations for Chronic Wasting Disease

New, quicker test methods for assessing CWD are also being developed to track and contain the spread of the disease. Currently, the only way for deer to be tested for infection requires submitting tissue from dead samples for lab work. Dr. Peter A. Larsen, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota’s College of Veterinary Medicine, is working to repurpose a tool for testing humans for Cruetzfeldt-Jakob Disease, a fatal prion infection like CWD. Developed in 2007, the Real-Time Quaking Induced Conversion (RT-QuiC) test is sensitive enough to virtually eliminate false negatives.

“Many labs have independently confirmed RT-QuIC accuracy in both human and animal prion diseases,” Dr. Larsen said. “The test is so sensitive that you could take one tablespoon of these (for example, a CWD prion) and mix it in 400 Olympic size swimming pools that have these (regular proteins) in it. That test could pick that up. That’s how sensitive it is.”

The RT-QuiC can be used to detect prions in deer meat, skin, mucus, blood, urine, semen, feces, water, soil, plants, and insects. “If you catch it super early and you live test, you could cull the animal and then go into monitoring with the sentinels and see if you effectively got in front of the situation,” Larsen said. “The caveat with all of this, if you go into an operation where CWD has been cooking for too long, you’re not going to get in front of it. It’s too late.”

Transmission to Humans Still a Question

Whether Chronic Wasting Disease is transmissible to humans remains a question vexing researchers. The disease is, functionally, no different than any other prion illness. Human prion diseases, like Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, act on the nervous system in much the same way CWD contributes to invariable cervid fatality: It destroys brain tissue, impairing movement and organ function, causing a wasting death.

It’s well established that animal-borne prion disease can jump the transmission barrier and infect humans. Such was the case with Bovine Spongiform Ecephalopathy (BSE), more commonly known as Mad Cow Disease. The disease first infected humans in the United Kingdom. In 1986, an outbreak killed 178 people and resulted in over four million cattle being slaughtered. The outbreak was believed to have been caused by beef processing plants mixing cattle feed with the meat and bone meal of other dead cows, infecting the animals before they were slaughtered for human consumption.

By changing feeding and slaughtering practices, Great Britain eventually contained the disease. Today, very few cases are diagnosed. The U.S. took a proactive approach to preventing BSE transmission to humans in the mid-2000s, with the USDA banning sick and injured cattle meat from the human food supply and enacting a stringent, nationwide surveillance program for beef prions.

Research on Cross-Species Infection Conflicted

Knowing the implications of prior species spillover, researchers have endeavored to confirm the integrity of the species barrier separating CWD from human transmission. One meta-analysis reviewed prior studies and found that several have shown nonhuman primates could be infected with CWD, while yet more studies showed infection through exposure was impossible. The most concerning study, though, suggested that transmission remains possible: When four macaques were dosed with CWD prions through oral ingestion, two went on to develop disease. These results concern researchers the most, as the transmission route and the primate species represent the most realistic path to infection for humans.

With one case of CWD recently found in Yellowstone National Park, the alarm is again being raised about the potential for cross-species infection. Dr. Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota who studied Britain’s BSE outbreak, calls the spread a “slow-moving disaster.” Dr. Cory Anderson, a CWD researcher under Osterholm, echoes the sentiment. “The BSE [mad cow] outbreak in Britain provided an example of how, overnight, things can get crazy when a spillover event happens from, say, livestock to people,” Anderson says. “We’re talking about the potential of something similar occurring. No one is saying that it’s definitely going to happen, but it’s important for people to be prepared.”