Gun “Buy-Back” Scalability

Oleg Volk 11.28.17

“Bring in your unwanted guns!” “No questions asked, no tracing attempted.” “Get cash for weapons.” The concept of guy “buy-backs”–as if the people offering money (or more often store cards) owned them to buy “back” in the first place–is pretty old.

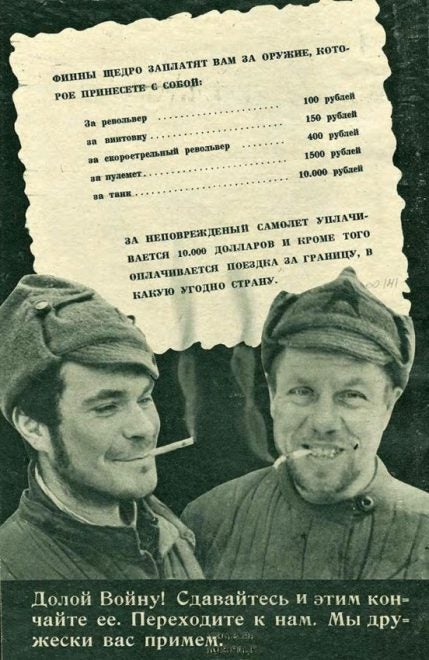

The above Finnish leaflet from the 1939 Winter War against the USSR offered money to Soviet soldiers for surrendering with their weapons. Few were in a position to take them up on the offer.

Modern Americans actually can sell their guns at such turn-in events. Those who do generally have no idea of the value of their firearms. The 22 rifle at the top of this page is collectible, even though it doesn’t look fancy. Its value at a gun show would far exceed the price paid by politically-motivated buyers. Some guns that end up at such events are diverted into private collections of police officers or other participants, while other firearms–sometimes uniquely-valuable historic pieces–are destroyed. In any case, people who sell their guns at “buy-back” events are almost never criminals. Criminals don’t let go of their tools of the trade.

The theory that removing guns from the general public reduces accidents and crimes of passion has no supporting evidence.

Anti-gun activists think buying guns back from the population can be scaled to include most of the guns in a country or even the world. That shows an utter ignorance of basic economics. We have seen going prices on basic AR15 carbines and AK47 semi-auto clones double over a few days purely on the news of Obama getting elected president. The actual number of such guns available was rising rapidly, yet the prices rose as demand outstripped supply. How would the prices change if the number of guns available for purchase actually shrank?

1930s Mosin-Nagant rifles were once available for about $70. A decade later, with the supply drying up, they command over $200 each. Keep in mind that the total number in circulation is still rising (just slower than before) and many functional substitutes are available.

The classic car market is the best illustration of how scarcity affects prices. How much does a 1965 Mustang cost, now that fewer of them are available?

The theory held by the anti-gun activists is that a person who paid $1,000 for an AR15 would give it up for destruction for $200. Part of that money would come from the former gun owner’s own taxes. A great deal, right?

Let’s say they actually offer whatever sticker price was on the gun, $250 for a 22 rifle and $1,000 for an AR15 and so on. Could they get a significant number of people to sell their guns? No.

The reason is that the worth of an object isn’t fixed. If I have ten rifles, I might be willing to sell the first one for $1000, especially if I don’t need that particular one for a specific purpose. Once I’m down to nine, I wouldn’t sell the next one unless I could get a higher price, as the marginal value increases. Moreover, my cost to replace that ninth weapon with something more suitable would also go up.

Once down to two rifles, I would demand a fortune for the second-to-last gun–20 or 30 thousand dollars wouldn’t be unreasonable, if I was willing to sell at all. That’s very common with NFA-regulated automatic weapons due to artificially-created scarcity. My last rifle would not be for sale at any price. So the price offered would have to go up exponentially as even a small fraction of privately-held weapons got bought up. There literally is not enough money in the world to buy every privately-owned gun in the USA, as the value of each remaining firearm would increase beyond the financial resources of all non-gun-owners combined.

Removing guns from the citizenry also presupposes a cessation or reduction of retail availability of replacements. If such a restriction was announced, the perceived value of currently-held guns would skyrocket and “buy-back” events wouldn’t get even the trickle they are getting now. Why sell for $200 when any neighbor would give you a grand? So such programs would have to be backed by viciously-enforced draconian laws against private sales. At that point, a country-wide ammo turn-in event might happen, with the bullets ending up inside the bright minds behind the idea. The only reason that hasn’t occurred already in places like New York City is the ability of gun owners to easily travel to less-retarded jurisdictions.

Further, since the definition of “gun” at such events has been pretty nonspecific, people have been turning in home-made firearms and making a nice profit from the transaction. Not being firearms enthusiasts or experts, anti-gun activists and their official supporters can’t tell the difference between a 22 Short revolver of minimal practical value and something that’s actually a worthwhile firearm, so they often overpay at current values.

Finally, we must realize that because the anti-gun side will tell a lie as easily as breathing, we can be certain that at least some of them will use any “buy-back” operation to gather intelligence and to note who brings what with the intent to raid those sellers later and steal the rest of their arms.