How to Evaluate Blade Shapes

Tony Sculimbrene 11.28.13

There are a wide variety of blade shapes out of there, and new ones are emerging all of the time. Some new blade shapes and grinds are, well, entirely aesthetic, while others, like the Besh Wedge, are genuine performance innovations. Having all of these choices can lead to indecision. In an effort to cut through (how punny!) all of these options, I am going to lay out a method of evaluating blade shapes.

All knife blades do essentially three things: pierce, slice, and chop. Most tasks are not pure versions of these tasks, but a combination of two of them. A snap cut, like those used in knife fighting, is a combination of a chop and slice. Whittling is another combination of chopping, lots of pressure, and slicing — very little movement with a drawing cut. Figuring out what kind of cutting you are going to do will tell what kind of blade shape will work best.

Before I get into specifics, let me lay out a principle that seems to transcend all of life: simplest is best. Wanna win a race? Go from Point A to Point B via the simplest route: a straight line. Wanna persuade a jury? Make the simplest, clearest argument. It’s hard to hide things when your argument is simple. Wanna get a good and useful knife? Avoid all of the beeps and borks of a silly blade shape or grind and keep it simple. Eliminate unnecessary complexity. Always.

In an EDC knife, you will almost always be doing slice cuts of some kind or another. There are very few tasks that require you to chop and even fewer still that require you to pierce. As such you’d do best to emphasis those shapes that promote slicing ability.

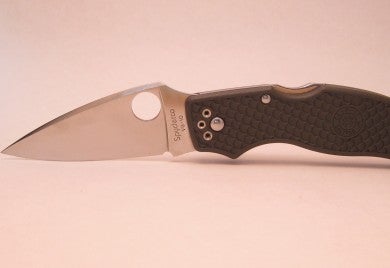

Here is one of my favorite slicing blade shapes, Spyderco’s classic blade shape:

That’s the blade on the Spyderco Paramilitary 2, one of the hottest production knives on the planet right now. Look closely and you’ll see quite a few subtle things that make this an excellent EDC blade shape. The tip is very sharp and relatively thin, which is bad for stabbing but good for starting slicing cuts like when opening a package.

Next there is a substantial amount of belly or curve in the blade, more so than, say, this knife with its leaf shaped blade:

Above is the Caly Jr, a great EDC knife, but not a great EDC blade shape. The difference in belly is pretty remarkable, especially when cutting. As you cut through material, the belly promotes a rocking action and that allows the blade to move back and forth (the draw cut) but also up and down a little. This makes for an excellent slicing tool. Belly also adds length to the cutting edge, as the curve is longer than a straight line would be. This gives you more edge to cut with, allowing you to use your knife longer and spread out wear over a larger surface.

But the greatness of the PM2 blade continues. As the blade comes out of the belly, it straightens out at an upward sloping angle, making the straight portion of the edge cut material at a more aggressive approach. This negative blade angle is why recurves cut so well. Instead of approaching the material head on, the recurve forces the material into the cutting edge at an angle, and that angle provides more leverage and a more aggressive cut. But recurves suck to sharpen, so the PM2 cheats. It gives you the flat edge that is easy to sharpen, but puts that edge at an angle to the material to give you the advantage. This effect is slight in the PM2, but here is another knife that does the same trick (and also has a superlative blade shape): my custom Gedraitis Small Pathfinder with its clip point blade:

On this knife the negative angle is even more pronounced than on the PM2, and it works a little bit better for it.

Another blade shape that is very good at general utility tasks is the Wharncliffe blade shape seen here:

The Brous Silent Soldier Flipper has a very good shape to it. The tip is plenty strong and pointy, probably more so than those shapes shown above. It also has a very good cutting edge. The lack of the belly is part of the trade off of the shape. You get a strong, reinforced tip because of the straight edge, but that same edge eliminates the rocking and negative approach angle from the clip and drop points shown above. One other benefit of the Wharncliffe shape is that it is very easy to sharpen on any kind of sharpener, from stone to rod system.

Related to the Wharncliffe is the sheepsfoot or modified sheepsfoot blade. Here is one on the Mini Grip 555hg:

This gives you a lot of the advantages of a Wharncliffe with a tiny bit of belly.

I also like reverse tanto blade shapes. Again, they provide a great deal of reinforcement of the tip (as that is the main feature of a tanto blade shape) with some belly. Here is an excellent version of the blade shape from the criminally underrated CRKT Eraser:

There are a few blade shapes I don’t like. I do not like double ground blades of any kind on an EDC knife. Ask a tactical person if they are good in those roles because I have no idea. Generally I have found them to be hard to use. Lots of cutting tasks are done better with a finger draped along the spine.

I’ve also found that I don’t like spear points, especially if they have a spine down the center of the blade. They look nice, but they really restrict the amount of belly you get. I don’t like recurves of any kind, as mentioned above, primarily because of their difficulty in sharpening, but also because they are very aggressive looking and not really public friendly. Finally, compound grinds are really quite useless unless you have a specific task or set of tasks. Tantos fit into this compound grind category, especially Americanized tantos. I don’t find the two points to be useful, and they are harder to sharpen.

The last tip I’d give you in evaluating blade shapes is to look at the cutting edge, not the spine. A lot of Anso’s blade shapes look really weird, but most are only weird in total and very normal along the cutting edge. One example is the Spyderco Zulu, shown below. It looks awful to sharpen, and it is a bit of a challenge, but really, the cutting edge itself is not that bad. Want proof? How about this little demo:

It’s mostly an illusion. This is really just a good ole drop point fancied up. It also happens to be one of my favorite blade shapes to use.

Don’t worry so much about the names of blade shapes. Figure out what you want to do with the knife and let that dictate what you buy. For general use, clip points and drop points are good. Wharncliffes are decent as well. A good reverse tanto is surprisingly excellent, given how few are on the market. Avoid recurves and compound grinds, unless your task demands them.